Stories in Indoor Climate Research – The Moment I Realized We’ve Been Doing It All Wrong

Posted: 9 February, 2026

In this blog, Dr. Asit Kumar Mishra highlights an epiphany about his research career that emerged during a training session on storytelling for communicating science.

Last October, I attended a workshop on storytelling in science communication. It was supposed to be a practical training session—tips for making research more engaging. But what it actually became was a mirror held up to my entire career as an indoor air quality researcher. As I sat through those sessions, something kept nagging me. The workshop emphasized narrative, personal connection, and how stories can humanize “facts”. And all I could think was: Why don’t we do this? That question sent me back through memory—to the pandemic, to the countless conversations I’d had with parents, community groups, and worried individuals desperately trying to understand the air in their homes and their or their children’s schools.

When People Actually Asked

During 2020 and 2021, I was busy on Twitter. I was dealing with direct messages and responses to posts from “strangers”. Parents worried about their children’s classroom. People asking about the air flow in their home that could help take care of sick loved ones while not getting sick themself. These weren’t formal academic inquiries. They were people scared, confused, and looking for answers. And here’s what struck me: their questions revealed something profound. They didn’t understand the basics. Not because they weren’t intelligent—they were incredibly smart and diligent people. But because nobody had ever explained it to them in a way that made sense.

There would often be conversations about ventilation ending at windows kept open on “nice days”. But people did not realize that opening windows sometimes isn’t enough, especially if the weather is nice and calm. No one was thinking of verifying the open windows with CO₂ level measurements or calculating air changes per hour. Why would they? Nobody had told a story of why this mattered.

Conversations often veered into the impacts of poor air quality, beyond infections – poor concentration for children and office workers, asthma exacerbations, poor sleep quality. Often these conversations would end up at: “Why doesn’t anyone talk about this?” And at that point, I would not have a good answer.

The Research Exists—So Where’s the Understanding?

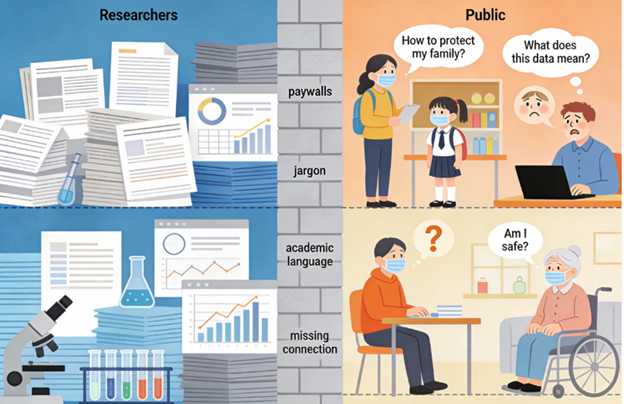

After the workshop, I faced uncomfortable questions. We’ve spent decades producing critical research about indoor air quality. We know people spend 80-90% of their time indoors. We know indoor pollutant levels can be two to five times higher than outdoor air. We know that by most conservative estimates, this contributes to 3.2 million premature deaths annually. We know simple interventions—better ventilation, air cleaners and filtration, consistent monitoring—dramatically improve health outcomes.

We’ve published it. We’ve presented it at conferences. We’ve written it in journals. Researchers have even done outreach events and workshops for lay audiences.

But the public? They more often than not don’t know any of it.

Sitting with that reality was uncomfortable. Our careful research, all those hours in the lab, all those datasets and peer reviews—wasn’t changing people’s lives. Not because the research was wrong, but because we were only talking to each other or when talking to the public, doing it wrong.

What’s Obvious to Us Isn’t Obvious to Anyone Else

Here’s what the October workshop taught me: what seems blindingly obvious to a researcher is completely invisible to someone living their everyday life. To me, it’s obvious you should care about the air you breathe. It’s obvious ventilation matters. It’s obvious this affects your health. But to the parent picking their child up from school? To the office worker struggling to focus? To the elderly person in a care facility? None of it was obvious. Because nobody had told them in a way that connected to their lives.

We hadn’t failed because we hadn’t done the research. We failed because we hadn’t told the story of the research. We have not bothered to give the public an insight into our life and why we felt what we were doing was so important.

What We Could Have Done Differently

During those pandemic conversations with parent groups, I was giving them data. Percentages. Technical terms. Research findings. What they needed was a story. What they needed was to be able to tell their own air quality related story. They needed to understand not just what clean air is, but why it matters—in their bedroom, their child’s classroom, their workplace. They needed to hear from someone real about why this work matters personally. They needed to know the researchers studying this stuff actually cared.

If I could go back, I wouldn’t start with findings. I’d start with a story. Maybe my own story—the moment. I realized indoor air quality mattered. A story about a child who couldn’t concentrate in a stuffy classroom, or a child unable to have a soft toy because of her damp home. Stories that the abstract concrete and the invisible visible.

The Commitment

So here’s my commitment: let’s tell our stories. Let’s share not just our findings, but our why. Let’s make indoor air quality personal, relevant, and impossible to ignore. The science is already there. Now it’s time to translate it into something people can actually use.

I’m deeply grateful to my DOROTHY-MSCA co-fund fellowship for recognizing that this work matters—for giving me the space and resources to engage in meaningful outreach efforts. This funding has made it possible to take the time to develop and refine indoor air quality stories, to attend workshops like the one that sparked this realization. Funding research is crucial. But funding researchers to communicate that research, to translate discoveries into stories that change minds and hearts? That’s equally important. And I’m grateful to be part of a program that understands that.